Most people, especially in the CS community, often think that machine learning is closer to web dev than wet lab. Well, that’s what I thought too in my early years at uni.

A Short Backstory

I started uni with an interest in web development. That’s what most people in my field were doing. AI was growing, but nowhere near as big as it is today. Back then, I thought of ML as just another branch of computer science, not so different from web development. Sure, it uses more maths and stats, but at the end of the day, it’s all still CS stuff. Or so I thought.

As time went on, I revisited my old interest in biology, something I’d picked up thanks to participating in my country’s biology olympiad. In my fourth semester, a friend asked me to join them in a course called Forensic Chemistry. Did I master the subject? Not quite. But I did enjoy the lab sessions. They were short, more like demos than structured experiments, but still fascinating. Around that time, I also volunteered as a lab assistant for the Basic Chemistry Laboratory.

All of this reignited my interest. I went on to attend various biology classes, including Diagnostic Microbiology, where we studied mechanisms for diagnosing diseases. The lecturer happened to be the head of the biology department, so I asked her if I could take Cell Biology. To my surprise, she said, “You can, if you want!”

Long story short, I ended up taking way more courses than I originally planned, thanks to a new minor programme introduced by my uni at the time. In total, I think I racked up more than 20 SKS (more than 30 ECTS).

Some of those were wet lab courses. So yes, I actually did wet lab sessions!

My classmates pipetting inside a LAF hood.

In my final semester, I took two major wet lab courses: Cell and Molecular Biology Project and Biomedical Cell and Tissue Engineering.

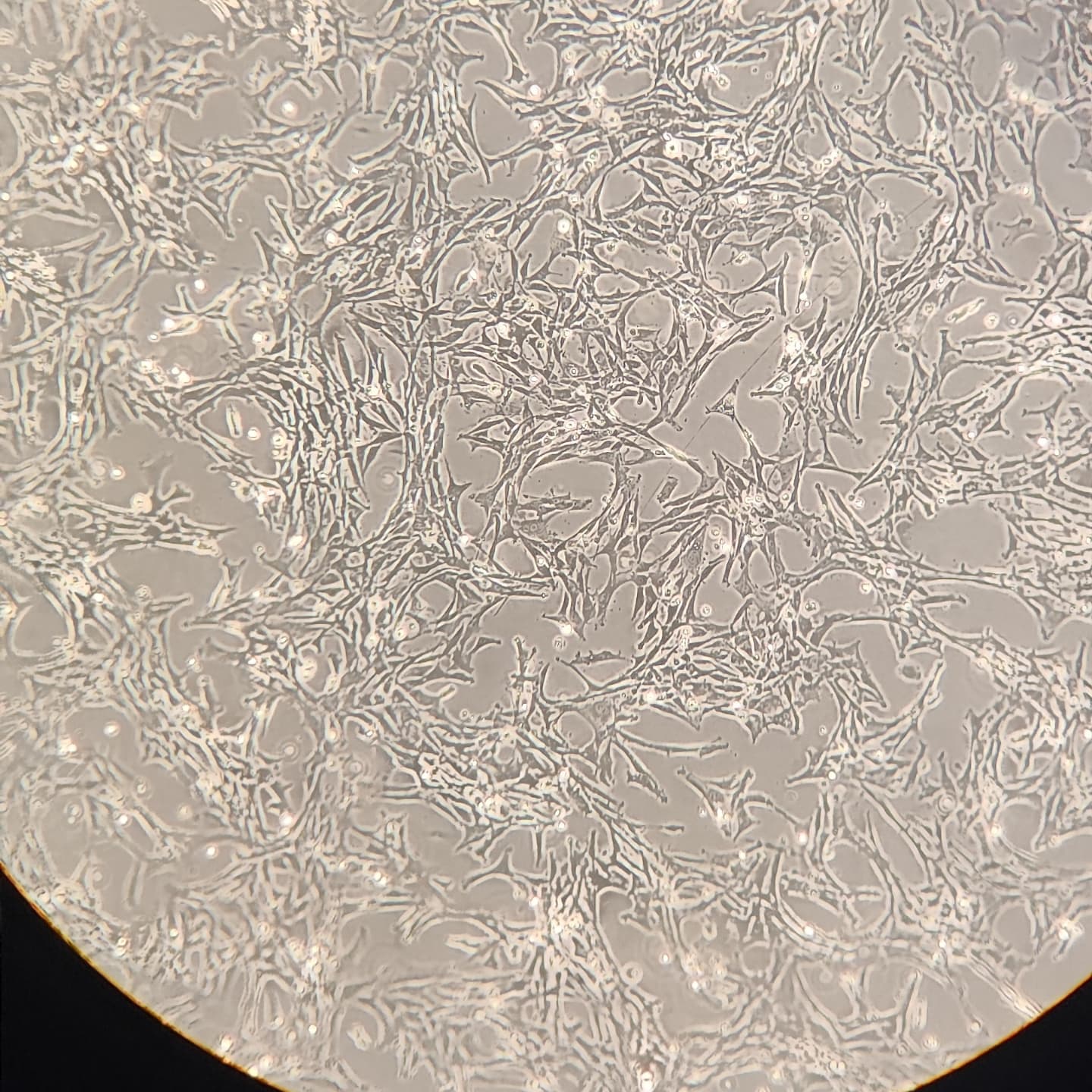

My beloved fibroblast culture (they’re dead now).

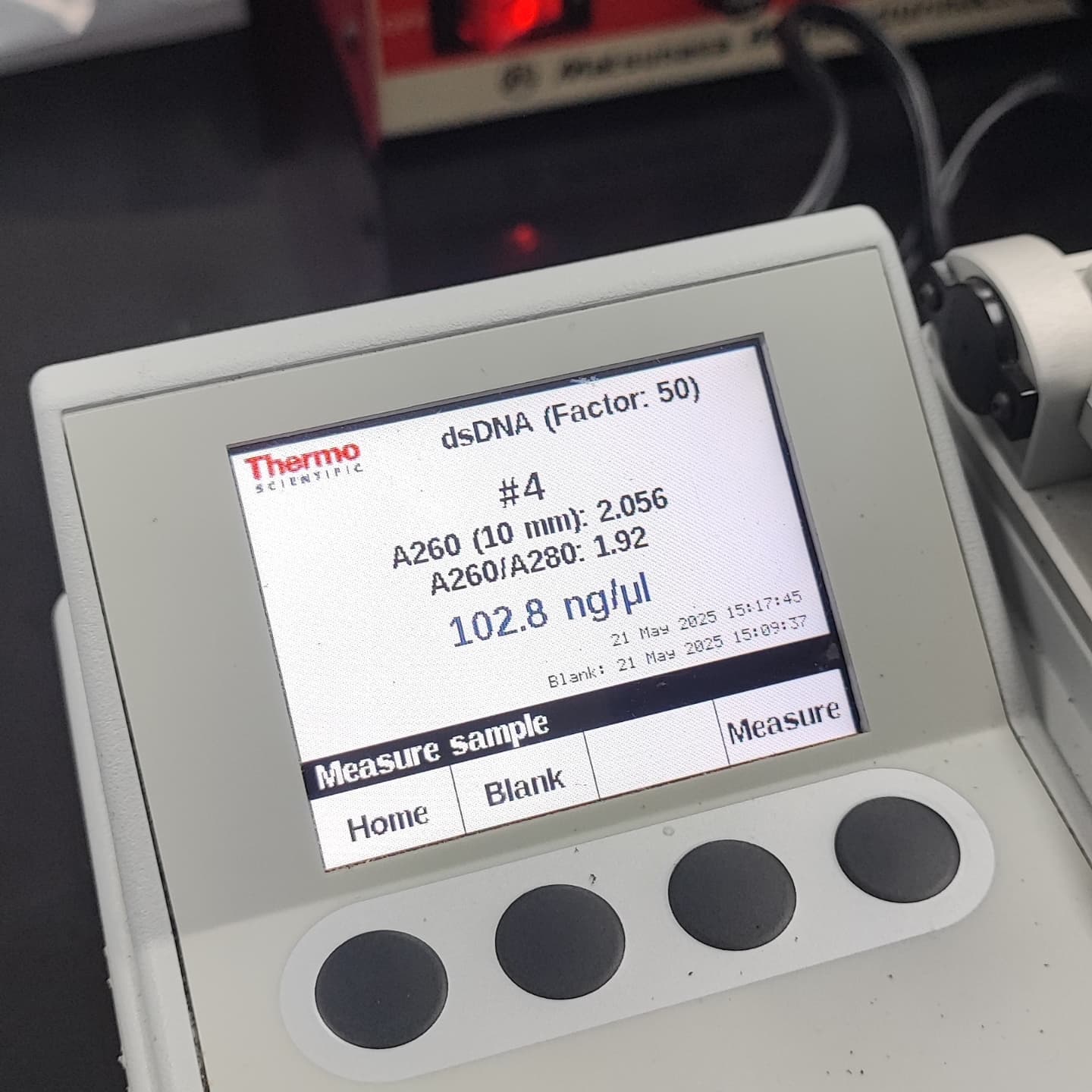

A terrible batch of plasmid I isolated from E. coli using the Zymo miniprep kit.

When it came time to choose a thesis topic, I couldn’t think of anything in my field that excites me. So, after some deliberation, I picked machine learning. Because, uhhh… I can just pick biology/chem as the domain. 😅

But here’s the twist: while working on my thesis, I realised that machine learning research has a lot more in common with molecular biology experiments than I had ever imagined.

Similar Epistemology

At first glance, the workflows of ML and molecular biology couldn’t be more different. One involves pipettes, the other involves writing code. But when you zoom out the epistemology is strikingly similar.

Both fields are driven by hypothesis and iteration. In molecular biology, you might hypothesise that a certain protein binds under specific conditions. You design an experiment, run it, and see if the results match your expectation. Most of the time, they don’t, and you tweak the conditions or redesign the experiment. In machine learning, it’s pretty much the same: you hypothesise that a certain model architecture or feature engineering trick will improve performance. You run the training, check the metrics, and most of the time… it doesn’t work. Heck, when I was doing my undergraduate thesis, some of my proposed solutions gave me worse results than the baseline. 🤣

Failure is the default. Progress happens when you refine the question, repeat the experiments, and tweak the variables. Any failure isn’t really a “failure”, it’s simply the next step in a longer feedback loop.

That is not the case with engineering-heavy fields such as web development. In those fields, you use known tools to solve known problems. Your job is to satisfy a set of requirements effectively and efficiently. Of course, large-scale systems in software engineering can have their own complexity. But in general, the mindset is often more deterministic: you’re building systems with known components toward a defined goal. For example, you know that if you write the correct CSS code, the button will be blue. In ML research, you hypothesize that adding a dropout layer might reduce overfitting, but there’s no guarantee, it could even make things worse. Nothing is ever guaranteed. This shared trial-and-error mindset also shows up in how both fields wrestle with opaque systems.

The Unavoidable “Black Box”

One of the biggest criticisms of modern deep learning is that models are often “black boxes.” A massive neural network can classify images with insane accuracy, but it’s incredibly difficult to pinpoint exactly why it decided a picture was of a cat and not a dog. We can poke and prod with interpretability tools, but the complete, intricate logic remains hidden within the millions or even billions of parameters.

Well, guess what? Biology is the original black box.

We know that if we introduce a specific drug to a cell culture, the cells die. Great! But how? We can hypothesise that it inhibits a particular enzyme. So we design an experiment to test that. But that enzyme is part of a larger signalling pathway, which is regulated by other pathways, which are influenced by the cell’s metabolic state, which is affected by… you get the idea. A living cell is an incomprehensibly complex system of interacting components. We can understand parts of it in isolation, but the emergent behaviour of the whole system is often a mystery.

I remember wondering why some batches of plasmid my friends isolated had little to no yield, despite being sourced from the exact same bacterial culture and processed with the same reagents, at the same bench, at the same time. It was a humbling lesson in hidden variables, one that felt oddly familiar when I’d stare at a training loss curve that refused to converge for no obvious reason.

To clarify, I’m not saying that producing mechanistic explanations of biological phenomena is impossible, but we must remain humble about how much we truly understand about the machinery under the hood. Time and time again, we keep getting proven wrong about our previous assumptions.

When dealing with such a complex system, we can only build models, and no model is ever perfect. We can refine our models to make them better, though, by incorporating new knowledge and discoveries. The goal is to slowly, piece by piece, shed a little more light into that black box. And because we are dealing with such opaque systems, the methods we use to verify our findings must be rigorous. This brings us to the next parallel.

The Sanctity of Controls and Baselines

If you walk into a biology lab and present results from an experiment without proper controls, no one would take your results seriously. Every experiment needs a negative control and a positive control. They are your sanity checks. They prove that your reagents aren’t contaminated, your equipment is working, and your experimental setup can actually produce the effect you’re looking for. Without them, your results are meaningless. For example, if your treatment produced no result, was it because it actually produced no result, or because you used the wrong reagent? If your treatment did produce a result, is it really because of the treatment and not due to environmental contamination?

This principle maps one-to-one with the world of machine learning. Your baseline is your negative control. It’s the simple, sometimes even “dumb,” model that you must outperform. If your fancy, multi-headed attention transformer can’t beat a simple logistic regression model on a classification task, you don’t have a result: you have a problem. Similarly, comparing your model’s performance to the current state of the art (SOTA) is your positive control. It demonstrates that you’re in the right ballpark and that your metrics are comparable to established work.

This extends even further. Since we agreed that both ML and molecular biology experiments deal with complex systems, we need to limit the number of variables to produce meaningful results. For example, we may try to use the exact same amount of reagents, the same strain, and the same procedure. Likewise, in ML we may fix the seed, hyperparameters, and dataset.

However, there is a degree of stochasticity, or randomness, that we just have to accept.

In biology, cells may not always behave the exact same way even if given the same treatment. Genetic variation can also cause issues. Not to mention things such as pipetting errors, slight deviations in reagent formulations, etc. That’s why we need both biological and technical replicates. We then perform statistical analysis to make sure our results are significant compared to the other treatments.

That very same mental model applies to ML experiments too! Model performance is tied to the inherent stochasticity of processes like weight initialisations, seeds, the path taken by the optimiser during gradient descent, the batch being loaded, how the split is performed (if done randomly), and even the order of operations by the GPU during the training. Hence, ideally, we need replicates and statistical analysis too. This is one of the reasons why reproducibility is such a hot topic in ML right now.

So, What’s the Point?

The tools may be different, but the core scientific mindset is strikingly similar. Both fields are profoundly empirical. They thrive on iteration, tolerate failure, and demand rigorous validation.

For me, this realisation was a bridge. Since my main background in college was computer science, people in CS often had a different mindset. Many of the problems we faced were more engineering-oriented. We were expected to solve known problems with known tools. Projects were like a zero-sum game: either you succeeded in fulfilling the requirements, or you didn’t.

The projects being developed within the CS curriculum were also often quite deterministic. I mean, that’s what we like about computers, right? They do what we tell them to do. Hence, statistical analysis was rarely done. People often just ran a test, gathered the result, and reported it. Meanwhile, ML problems are rarely deterministic. Each training run can produce wildly different outcomes, so the same approach simply doesn’t work.

So, having taken molecular biology courses, especially the wet lab ones, really helped me transition into a completely new mental model. One that is far more suited to the field of machine learning research.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading. This might not mean much to others, but for me, it’s what made me realise the benefit of interdisciplinarity, even at the undergraduate level. It taught me that the most powerful tools aren’t just found in a specific discipline, but in the ability to borrow lenses from others to see our own problems in a new light. 😁

Have you found surprising overlaps between fields you study? I’d love to hear.